Can human-dog friendship withstand the ‘virtual reality’ paradox?

May 5, 2024

Dr. Nishant Kumar

DBT/Wellcome Trust UK India Alliance Fellow (National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR & University of Oxford)

Faculty, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, New Delhi

In the Anthropocene epoch, many species struggled to cope with the rapid changes in their environment, including changes to their habits and habitats.

We are witnessing an intriguing paradox in the urban mosaic of human-animal coexistence, against the backdrop of widespread decline in biodiversity. Our physical interactions are now vastly limited to a few synurbic species – dogs, cats, cows, pigeons, monkeys and crows. On the other hand, we have remarkably diversified ways in which we connect in the virtual realm, from watching live feeds of wildlife to following pets’ daily antics on social and other media platforms.

This paradoxical urban fusion of physical and virtual realms is triggering paradigm shifts in coexistence benchmarks. Often, our attempts to craft comprehensive policies to address human-animal conflicts fall short, e.g., temporary displacement, street dog adoption, or birth control measures to curb dog populations and rabies spread. Such mitigation measures may be too broad to effectively address specific situations. We strive to create all-encompassing policies, yet frequently fail to capture the full spectrum of on-the-ground realities and the emerging virtual nuances of interaction paradigms. We eventually come across stalemate situations leading to counterproductive outcomes.

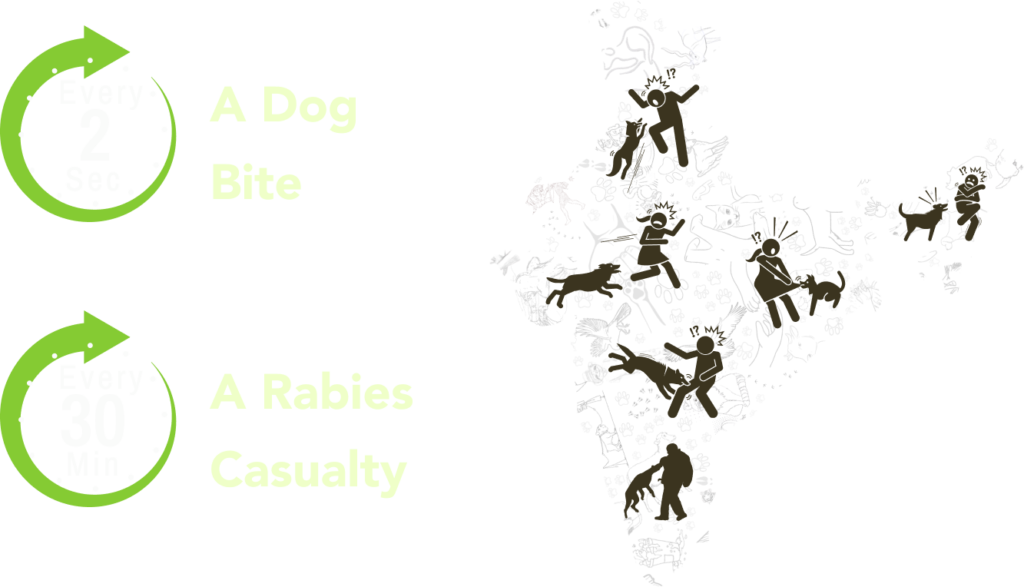

Amongst various developmental challenges we face in India, the issue of dog bites – which occur every two seconds – needs serious consideration, given that it’s bound to significantly contribute to Rabies, of which every 30 minutes, the country suffers a casualty. The frequent conflicts between humans and dogs on our streets highlight the need for a more nuanced approach.

In the Anthropocene epoch, many species struggled to cope with the rapid changes in their environment, including changes to their habits (slow-achieved behavioural adaptations) and habitats. Recent research indicates that behavioral misalignments in response to new stimuli have led to a decline in population in several species that are trying to adapt to anthropogenic changes. However, some species, known as ‘urban exploiters’ (such as free-roaming dogs), have developed a range of behaviors that are conducive to cohabitation with humans.

However, emotional bonds with animals can be challenging when they extend beyond physical proximity. Unlike humans, animals do not have the same socio-cognitive and cultural apparatus to fully comprehend or reciprocate these dynamic emotional ties. Instead, non-human animals rely primarily on their own social/cultural processes and biological instincts to navigate these newfound aspects of cross-species kinship. This discrepancy highlights relatively new cross-species relationships within rapidly changing urban landscapes. However, it is essential to note that issues and discrepancies in animal management often arise from a lack of understanding of how human and animal behavioural processes align. The similarities and anthropogenic differences between animals and humans are often overlooked in animal management, leading to the misguided belief that animals, as non-sentient beings, can simply be ‘handled’.

Intriguingly, many companion animal species have developed the ability to perceive and exploit individual humans or communities as sources of sustenance. These behaviours are intertwined with regional socio-cultural nuances, giving rise to corresponding animal cultures of opportunism. The perpetually littered streets in cities like Delhi serve as catalysts for such intricate relationships. As we continue to share our spaces with these creatures, it becomes imperative to understand and address the ecological implications of our coexistence. This coexistence is not merely a matter of space sharing; it is a complex interplay of behaviours, resources, and socio-cultural expressions that shape our urban ecosystems. Indeed, addressing human-dog conflict issues transcends the simplistic view of a two-species interaction problem. It necessitates an understanding of the intricate web of connections that link human activities, politics, history, socioeconomics, and urban planning across multiple spatiotemporal scales. This multifaceted approach is essential for fostering coexistence in our shared urban ecosystems. As we continue to navigate this complex landscape, it is crucial to remember that our actions today will shape the urban ecology of tomorrow.

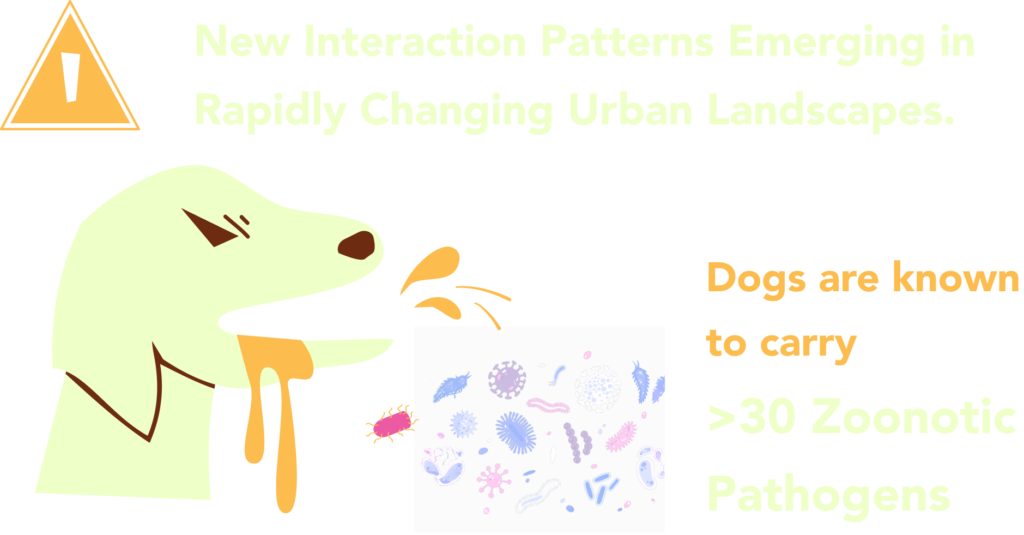

Dogs have indeed woven themselves into the fabric of our urban communities. However, their ubiquitous presence frequently sparks conflicts among humans. We must acknowledge that human-dog relationships have evolved to a stage where their connections often mirror familial ties (called kinship). People who regard pet/street dogs as family members often grapple with understanding the potential adverse impacts such relationships can have on fellow citizens and wildlife. Actions or remarks by management that are perceived negatively cause significant distress to such people. Although dogs often face cruelty in the streets at the hands of insensitive people, sometimes the concerns of those who sympathise with dogs overlook the fact that human-dog conflicts have age, gender, or social class specificities. Navigating conflicts that arise at the human-animal interface requires empathy and compassion, given that co-existence is a constantly shifting goal in tropical urban areas. Recently, researchers have been examining unique interactions between different species and their influence on ecological patterns in behaviour and population, specifically in the Global South where coexistence dynamics are distinct in lively cities teeming with diverse life forms. In cities like Delhi, there is a unique combination of western infrastructure and regional cultural ethos. This results in people living alongside and feeding dogs and other commensal animals as part of their daily routine. While sharing living space with these animals can be advantageous due to the various ecosystem services they provide, there are also potential public health implications that need to be considered. The rapid transformations in urban ecosystems are leading to new interaction patterns, which can cause rapid adverse impacts by creating new host-pathogen interactions. Like recent pandemic events, dogs are known to carry more than 30 zoonotic pathogens. This underscores the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health.  30 Pathogens – Thinkpaws” width=”569″ height=”297″>

30 Pathogens – Thinkpaws” width=”569″ height=”297″>

The coexistence of humans and free-roaming dogs, spanning from quaint villages to bustling megacities, presents a myriad of intriguing facets ripe for scientific and social exploration. Foremost among these are the ritualistic feeding practices deeply ingrained in Indian religious beliefs. These practices sustain urban animals such as dogs, kites, and macaques and significantly influence their movement patterns and aggression levels. This intricate interplay between religious customs, human-animal interactions, and urban ecology necessitates careful consideration for effective policymaking and urban planning.

Secondly, the heterogeneously developed metropolis of Delhi fosters a diverse array of relationships between humans and animals, sculpted by both biological and socio-cultural factors. An often overlooked yet crucial aspect is the ecological impacts of waste-based biomass, which significantly influences the behaviour of several opportunistic organisms. Acknowledging the ecological impacts of waste management on urban life forms is a significant step towards creating sustainable futures. It is our responsibility as urban stewards to create a livable environment for all, including non-human stakeholders. This involves addressing the critical aspect of waste management, which traditionally incorporated non-human agents. To tackle these compassion-conflict tensions at hand, it is essential to undertake a research-based intervention that meticulously examines the spatially explicit links between behaviours and demographics of opportunistic animal scavengers.

Third, the ongoing urbanisation in tropical cities brings about substantial infrastructural changes and gentrification, impacting both the physical landscape and socio-economic dynamics. These developments can displace communities, altering the availability of food resources and consequently influencing the behaviour of non-human species. Lastly, the oversight in slum rehabilitation policies, and biomining of landfills, such as those implemented by the Delhi Development Authority and municipality, underscores a disconnect in recognising the interdependence between human and non-human populations. Overlooking the well-being of free-roaming dogs during urban development initiatives may lead to unintended consequences, posing challenges to public health and animal welfare. Further research is indispensable to uncover the underlying impacts of environmental and regional infrastructure factors on the human-dog relationship. This understanding will pave the way for more effective strategies in shaping this coexistence within shared urban ecosystems.

Key References

- Albuquerque, N., Guo, K., Wilkinson, A., Savalli, C., Otta, E., & Mills, D. (2016). Dogs recognize dog and human emotions? Biology Letters, 12(1), Article 1.

- Bhattacharjee, D., Sau, S., & Bhadra, A. (2018). Free-ranging dogs understand human intentions and adjust their behavioral responses accordingly. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 232.

- Cavé, J. (2014). Who owns urban waste? Appropriation conflicts in emerging countries. Waste Management & Research, 32(9), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X14540978

- Clutton-Brock, T. (2009). Cooperation between non-kin in animal societies. Nature, 462(7269), Article 7269.

- Doron, A. (2021). Stench and sensibilities: On living with waste, animals and microbes in India. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 32(S1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/taja.12380

- Fitzpatrick, M. C., Shah, H. A., Pandey, A., Bilinski, A. M., Kakkar, M., Clark, A. D., Townsend, J. P., Abbas, S. S., & Galvani, A. P. (2016). One Health approach to cost-effective rabies control in India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(51), Article 51.

- Gowda, V. D., M. M. Shankare. (2021). Slum Re-development, Differentiated Resettlement, and Transit Camp: The Kathputli Colony Rehabilitation Project in Delhi 1. In Urban Resettlements in the Global South. Routledge.

- Hendrix, P. F., Parmelee, R. W., Crossley, D. A., Coleman, D. C., Odum, E. P., & Groffman, P. M. (1986). Detritus Food Webs in Conventional and No-Tillage Agroecosystems. BioScience, 36(6), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.2307/1310259

- Jones, D. N., & Thomas, L. K. (1999). Attacks on humans by Australian magpies: Management of an extreme suburban human-wildlife conflict. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 473–478.

- Kumar, N., Gupta, U., Jhala, Y. V., Qureshi, Q., Gosler, A. G., & Sergio, F. (2018). Habitat selection by an avian top predator in the tropical megacity of Delhi: Human activities and socio-religious practices as prey-facilitating tools. Urban Ecosystems, 21(2), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-017-0716-8

- Kumar, N., Gupta, U., Malhotra, H., Jhala, Y. V., Qureshi, Q., Gosler, A. G., & Sergio, F. (2019). The population density of an urban raptor is inextricably tied to human cultural practices. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286(1900), 20182932. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2932

- Kumar, N., Jhala, Y. V., Qureshi, Q., Gosler, A. G., & Sergio, F. (2019). Human-attacks by an urban raptor are tied to human subsidies and religious practices. Scientific Reports, 9(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38662-z

- Kumar, N., Qureshi, Q., Jhala, Y. V., Gosler, A. G., & Sergio, F. (2018). Offspring defense by an urban raptor responds to human subsidies and ritual animal-feeding practices. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0204549. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204549

- Kumar, N., Singh, A., & Harriss-White, B. (2019). Urban waste and the human-animal interface in Delhi. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(47), Article 47. https://www.epw.in/journal/2019/47/review-urban-affairs/urban-waste–human-animal-interface-delhi.html

- Lamb, C. T., Ford, A. T., McLellan, B. N., Proctor, M. F., Mowat, G., Ciarniello, L., Nielsen, S. E., & Boutin, S. (2020). The ecology of human–carnivore coexistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), Article 30.

- Markandya, A., Taylor, T., Longo, A., Murty, M. N., Murty, S., & Dhavala, K. (2008). Counting the cost of vulture decline—An appraisal of the human health and other benefits of vultures in India. Ecological Economics, 67(2), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.04.020

- Nyhus, P. J. (2016). Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41, 143–171.

- SCS Engineers, and A. A. (2017). No TitleGhazipur Landfill Rehabilitation Report,” prepared for East Delhi Municipal Corporation, on behalf of US Environmental Protection Agency and Climate and Clean Air Coalition Municipal Solid Waste Initiative.

- Tarazona, A. M., Ceballos, M. C., & Broom, D. M. (2019). Human Relationships with Domestic and Other Animals: One Health, One Welfare, One Biology. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 10(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10010043

- Våge, J., Wade, C., Biagi, T., Fatjó, J., Amat, M., Lindblad-Toh, K., & Lingaas, F. (2010). Association of dopamine- and serotonin-related genes with canine aggression. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 9(4), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00568.x